According to Grammarly:

A phrase is a small group of words that communicates a concept but isn’t a full sentence. You use phrases in your writing and your speech every day. There are lots of different kinds of phrases, some of which play a technical role in your writing and others that play a more illustrative role. No matter which role a phrase is playing, it’s achieving one simple goal: making your sentences richer by giving your words context, detail, and clarity.

https://www.grammarly.com/blog/phrases/

While this definition is specific to grammar, the same concepts apply in music.

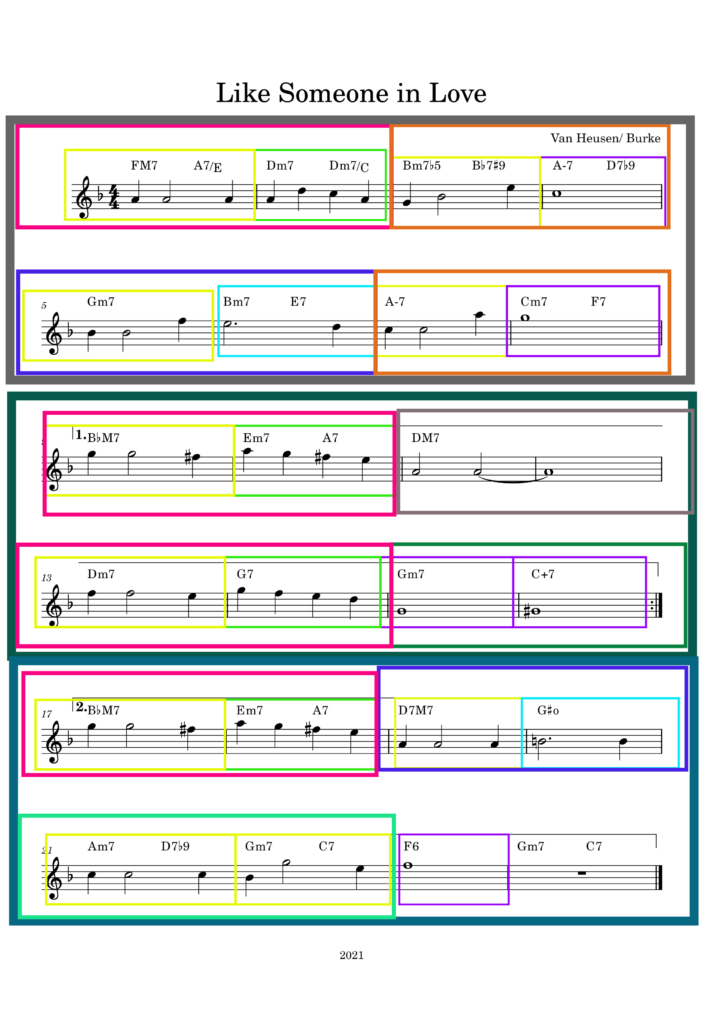

Phrases are the smallest complete units of musical thought that end with a cadence. They are usually two, four, or eight measures long but the lengths may vary.

An understanding of phrases is important to realize the nuances of a piece of music such as how the piece is divided and tension and release points. Understanding these components of a composition help you perform these nuances so that everything flows as the composer intended. Just like phrases in written or spoken language, phrases give your musical performances and compositions context, detail, and clarity.

Motives

Motives are the smallest recognizable musical idea, they gain their characteristics through specific uses of pitches, the contour of a melody, and even the rhythm. While the motive is a full idea, it rarely contains a cadence. A musical idea is categorized as a motive only when it is repeated exactly or in a varied form – think transposition

Motives can be all about the rhythm of an idea while the intervals and the contour of the motive change or the motive can be defined by a melodic contour – keeping a specific shape but varying the rhythm and interval.

Labeling Motives

- Motives are labeled with numbers or lowercase letters from the end of the alphabet

- The letters at the beginning of the alphabet are reserved for phrases and larger units

- Motives can be named descriptively: the arpeggiated motive, the neighbor-note motive, the dotted motive, the descending-thirds motive, the extended scale motive

Variation of Motives

Variety is a spice of life; this is true, especially in music. Motives can be changed up in a few different ways:

- Transposition occurs when a motive appears on another scale degree

- Inversion occurs when the direction of each diatonic interval is reversed ( keep the order of interval sizes the same, but reverse each interval in direction, e.g. an ascending third becomes a descending third)

- Extension occurs through repetition of a portion of a motive to make it longer

- Truncation occurs when the motive is made shorter by removing a portion from the end

- Fragmentation occurs when a small, yet recognizable, portion of the original motive is repeated with any of the other methods of variation listed above

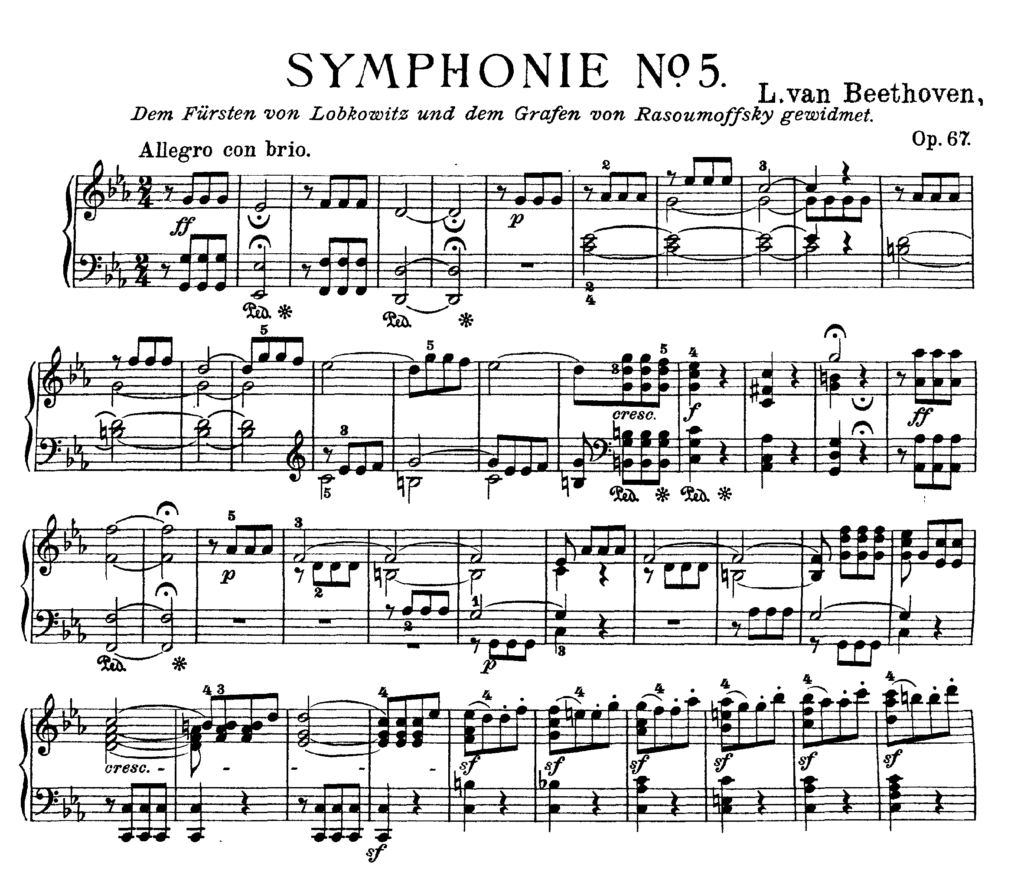

The Sentence

A sentence is usually an 8 or 4 bar unit with the smaller units – subphrases – divided in bars as 2 + 2 + 4 or 1 + 1 + 2, respectively. The first two units do not end with a cadence, but the third unit brings a sense of closure to the phrase.

A motive – the basic idea – is stated in the first unit and is usually over the tonic harmony. The motive is restated in the second unit; it may be identical to the first statement, but it is usually varied or transposed. This restatement is usually over a dominant harmony or a tonic expansion. These first two units are called the presentation. Finally, in the third unit, the motive is decomposed and developed with a faster harmonic rhythm, that moves toward the cadence – often a half cadence or perfect authentic cadence. This final unit is called the continuation.

The term “sentence,” is reserved for cases where the presentation phase is harmonically incomplete, and the true cadence is only found in the continuation.

The Period

Periods are formed when there are two phrases – one with a harmonically weak cadence and the other with a stronger cadence. The first cadence is usually a half cadence or inauthentic cadence, while the second is usually a perfect authentic cadence. The first phrase is called the antecedent and the second is called the consequent.

Phrases in a period can be symmetrical – both phrases would be the same length – or the phrases can be asymmetrical with both phrases being different lengths.

Sentences may be embedded in periods.

- Parallel Period (a a or a a’)

- Contrasting Period (a b)

- Modulating Period (changes keys)

- Three-phase Period (a a b, a b b’, a b a’ or a b c)

- Double Period (a b a’ b’)

Phrase Rhythm

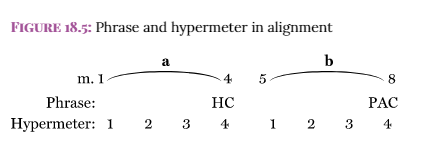

Phrase Structure and Hypermeter

An understanding of motives, phrases, sentences, and periods allows us to give a musical line direction and perform it without sounding choppy and amateurish.

To find the rhythm and flow of a piece you basically have have two strategies:

One approach is harmonic: locate the cadences, then move through the harmonies in th emiddle of th phrase toward the harmonic goal. The other, a metric strategy, requires you to focus on larger hepermetric levels.

The Musician’s Guide to Theory and Analysis, Third Edition, p. 377

Hypermeter interprets groups of measures as beats within a single measure. The way hypermetric structure and phrase structure align is known as phrase rhythm. When you understand the relationship between hypermeter and phrase structure you can then begin to treat phrases as though they were one bar like successive waves of sound washing over the listeners.

Youtube Resources

This video from Music Matters discusses how to come up with a motif. The process of constructing a motif is unpacked during this music composition lesson; the author explains how to come up with a musical motif and how to ensure it fits within the harmonic structure.

This video, by Dr. Kati Meyer Music Theory describes the two-part phrase structure known as the period. It covers parallel, similar, contrasting, modulation, three-part, and double periods.

In this video, Dr. Kati Meyer Music Theory continues the discussion by unpacking the thematic structure known as the sentence: Presentation and Continuation; Basic idea; and fragmentation. She also discusses three variants of basic idea repetition in the presentation.

In this video, Donald Sloan discusses Phrase Structure and Motivic Analysis. The discussion includes phrase and harmony, sub phrases, and motives.

In this video, David Bennett Piano discusses motifs and their use throughout musical history to create catchy melodies.

I enjoyed this video by Nahre Sol. She explained how she analyzes music and how it helps her to create her own music.

Practical Use